With the launch of the new and improved Morikami.org we decided it was time to also intgrate our blog. You can still find all the same great content, including an archive of our past posts, at www.morikami.org/by-morikami. We hope to see you over there soon!

Hallowed Trees: The Furniture of George Nakashima

Guest Blog by Susanna Brooks, Curator of Japanese Art

“I’m essentially a druid. I believe that there are ghosts in trees, and in a very deep sense the tree is more God-like that man….There is a spirit in tree, bouncing up and down in the grain of a tree.“

Opening this autumn at Morikami Museum is Japanese Design for the Senses: Beauty, Form, and Function, an exhibition that brings together a wide array of works that explore elements of form in Japanese design. Included in this exhibition are four furniture pieces made by George Nakashima (May 24, 1905 – June 15, 1990), a leading innovator of 20th century furniture design and a founder of the American craft movement.

At first glance, Nakashima’s simple forms reflect an austere, meditative sensibility that pays a heartfelt tribute to Shaker furniture design, a style that informs much of his work. Upon closer inspection, the wood exudes a kinetic energy that seemingly stems from the jaunty interplay of its spirited outlines and swirling, pulsating burls, tenderly paying homage to the tree trunks and roots from which it was cut.

Coinoid Bench; Dining Room Table and 6 chairs; Desk

Walnut and hickory; walnut, rosewood, and hickory; walnut and metal

1983; 1984

Collection of Morikami Museum

An American of Japanese ancestry, Nakashima was born in Spokane, Washington, but grew up near the Olympic Peninsula. The lush landscape of his home state, the wondrous forests of his youth, undoubtedly inspired Nakashima’s profound appreciation for trees and his interest in studying forestry at the University of Washington, Seattle.

During his coursework at the university, Nakashima became interested in structural forms and changed his major to architecture, earning his bachelor’s degree in 1929. The following year, he pursued his master’s degree in architecture at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), after which he traveled to France and earned a diploma at the École Américaine des Beaux-Arts in Paris. Nakashima spent a few years traversing the globe on a spiritual quest, making his way to an ashram in India, where he lived for two years as a monk before making his way to Japan.

In Japan, Nakashima met and worked with American architects Antonin Raymond (1888 – 1976) and Frank Lloyd Wright (1867 – 1959). Raymond had worked as Wright’s chief assistant during the construction of the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo. By way of Raymond’s introduction, Nakashima worked for Wright before moving on to become a lead project manager for Raymond’s firm. During his time in Japan, Nakashima studied traditional Japanese carpentry and furniture making. It was also in Japan that he met and married Marion Okajima (1912 – 2004), an American of Japanese ancestry who was teaching English at a private school.

Nakashima appreciated and related aesthetically to Raymond’s architectural approach, a style which married traditional Japanese design elements with innovative American materials and modes of construction. In 1935, Nakashima’s former guru in India, the distinguished yogi Sri Aurobindo, afforded Raymond the opportunity to bid on a major building project. When Raymond’s firm was selected to construct a dormitory at Aurobindo’s ashram in Pondicherry, Nakashima was made the lead designer/project manager. Completed in 1945, the ashram was named Golconde, after the nearby diamond mines. Golconde is the first building in India to use cast-in-place concrete, and among the earliest examples of sustainable modern architecture. The dormitory’s interior, a harmonious blend of wood, stone, and concrete, serves as a personal homage to Nakashima’s innate sensibility toward wood and his skillfulness as an architect, designer, and wood craftsman.

Photos of Golconde courtesy of American Institute of Architects (AIA) (http://www.aia.org/aiaucmp/groups/ek_public/documents/pdf/aiap080052.pdf )

During the time that Nakashima worked on the project, he reconnected to his spiritual practice and became a dedicated disciple of the ashram. The personal connection that he formed with the ashram pervaded every aspect of his work. The space and the materials used in its construction took on a deeper, more profound meaning. This intuitive approach would later come to inform Nakashima’s relationship with wood and his philosophy as a furniture designer/maker. Amid rising political tensions abroad, Nakashima and his wife returned to Seattle in 1939, and set up a studio and workshop, where Nakashima designed furniture and taught woodworking.

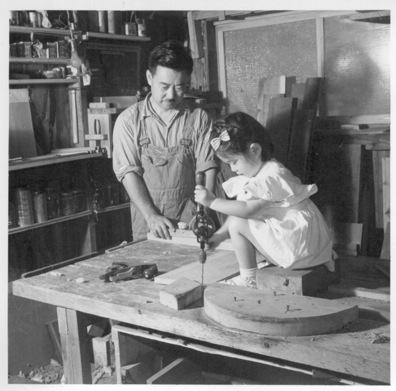

On February 19, 1942, just over two months after the United States declared war on Japan, President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 which called for the internment of all people of Japanese ancestry. From 1942 to 1946, between 110,000 to 120,000 citizens were forced to leave their homes and relocated to internment camps. Nakashima, Marion, and their small daughter, Mira, were interned at camp Minidoka in Idaho.

At Minidoka, Nakashima met and worked with Gentaro Hikogawa, a skilled wood craftsman. Under Hikogawa’s tutelage, Nakashima mastered the use of traditional Japanese tools and joinery techniques and developed his signature style: large-scale pieces composed of multiple, smooth-finished slabs of wood joined together with butterfly joints.

In 1943, after a lengthy petition process, Antonin Raymond was granted permission by the government to sponsor the Nakashima’s at his farm in New Hope, Pennsylvania. It was at Raymond’s farm, which doubled as a studio, that Nakashima explored the organic expressiveness of wood. For his pieces, he selected boards with natural knots, burls and figured grain. With Raymond’s guidance, Nakashima established his own studio and workshop, and his career as a furniture designer soared. He received commissions to design furniture for such high-end retailers as Knoll and Widdicomb-Mueller, as well as for wealthy residential clients.

Among Nakashima’s private clientele was Nelson Rockefeller. In 1973, Rockefeller commissioned Nakashima to make a few hundred pieces of furniture for his home in New York. This was a watershed moment for the George Nakashima name, as it quickly became synonymous with the best 20th century American furniture designers. The Rockefeller pieces exemplified the elements that made up Nakashima’s signature style: a harmonious blend of Japanese simplicity and functionality combined with the austere minimalism that is the hallmark of Shaker furniture design and the linear elegance of American Windsor style. His daughter, Mira, worked alongside him in the studio.

In 1983, Morikami Museum commissioned Nakashima to build the pieces that appear in the current exhibition. Mira assisted her father with the process. On view in the gallery are letters of the correspondence between Morikami Museum and the Nakashimas. The letters are accompanied by several detailed drawings of the pieces he planned to create for the Museum.

Since her father’s death in 1990, Mira Nakashima-Yarnall has carried on the Nakashima legacy, running the George Nakashima Studio in New Hope and preserving the integrity of her father’s original designs. In 2008, Nakashima’s studio and workshop was placed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Throughout the years that George Nakashima enjoyed his fame and success, much of it owed to his mentor and friend Antonin Raymond, he never forgot the teachings of Gentaro Hikogawa. In fact, and ironically, Nakashima credited much of his success as a furniture maker to the techniques he learned while confined at the interment camp. George maintained that the unhurried pace of daily life there slowed him down enough to reacquaint himself with the traditional Japanese tools and joinery techniques that he had been exposed to as a young man. He also credited Hikogawa for teaching him to approach his work with focus, discipline, and patience, and for pushing him to strive for perfection at every stage of construction.

In the autumn years of his life, George Nakashima shared the beliefs that shaped his life’s work:

“There’s a possibility of interrupting the sequence of life and death by doing something with a tree that will continue on. Trees, like all living objects, if they’re not utilized in a good way, will go back to dust…. I feel that every piece of wood has an exact usage, and finding this exact usage becomes my job. And I have to feel that it [the tree] has to be utilized to its utmost potential, otherwise it’s a let down for both myself and the tree. There is a partnership there that’s very important”

Quotes courtesy of the George Nakashima Studio (http://www.nakashimawoodworker.com/philosophy/ )

What is Obon? Exploring One of Japan’s Most Important Holidays

During the summer observance of Obon, families in Japan reunite to give homage and thanks to their ancestors, who have returned for a brief visit to the living. Many families set up special altars in their homes decorated with food offerings for these visiting spirits, which may include vegetables, dango (rice dumplings), noodles, and fruits. Candles, special paper lanterns called bon chochin, and incense may also be placed on the Bon Altar. Vegetable animals – a horse made from a cucumber or an ox made out of eggplant – serve as symbolic transport for ancestors to return to the otherworld. At Morikami, we set up a Bon Altar inside the museum to honor our ancestors, including George Morikami. We hope you’ll observe this tradition with us when you visit Saturday, August 16 or Sunday, August 17.

Throughout three days of festivities, communities gather for Bon Odori, folk dancing, to entertain the visiting spirits. Men, women and children dance around a platform stage called a yagura on which drummers and flutists perform. As the evening progresses, the singing and dancing become more animated. Lively street fairs complete with games, food, and shop stalls pop up in larger communities. On the final evening, the visiting spirits depart on a journey illuminated by farewell fires—floating paper lanterns. This ceremony is called tōrō nagashi.

While Obon is a traditional and religious Japanese holiday celebrated exclusively during the months of July or August, we offer a glimpse into Obon as it is celebrated in Japan, with Lantern Festival – a unique fall festival coming up Saturday, October 18. Tickets for members are on sale through August 31 and ticket sales open to the public on September 1. Tickets are expected to sell out and are only available online in advance at www.morikami.org/lanternfest. We hope you’ll join us at our most iconic annual event!

- Our Bon Altar for George Morikami

- Fruit and flowers at our Bon Altar

- Food at the Bon Altar for George Morikami

- The Yagura at Morikami’s Obon Festival in 2012

Guest Post: Four Masterpieces Joined by the Spirit of Water

Water 水 falls from above, and from below, 水 falls

Four Masterpieces Joined by the Spirit of Water

By Susanna Brooks, Curator of Japanese Art

It is summer, and the rainy season is upon us at Morikami. Rain falls practically every afternoon. The sky becomes dark and the rain falls fast and heavy, culminating into torrential downpours that draw everyone to the windows to take in the stunning, mesmerizing view of water falling from the sky and cascading down the rain chains, nourishing the plants, and dislocating the pebbles in the once-neatly-raked dry garden.

Rain is universally revered for its ability to create and sustain life and respected for the power it has to wound and raze nature when it falls hard and long. This entry provides an abbreviated exploration of the element of water as a meaningful motif in Japanese philosophy and art, primarily as the main subject of two famous 19th-century woodblock prints, which, in turn, share an affinity with two 19th-century Western masterpieces.

Water sustains all life, made evident by the fact that both the Earth and human body are composed of 70 percent water. For many cultures water holds spiritual symbolic meaning, with the natural attributes of water – its flexibility and adaption to change and transformation – equated to ideal human emotions and actions.

A precept of Japanese Buddhism holds water (水 sui, or mizu) second in importance to Earth in the cycle of the five elements of the universe (Earth, Water, Fire, Wind, and Nothingness). Representations of these five elements are present time and again in the design of Japanese architecture, stone lanterns, Buddhist temples and Zen-inspired gardens. In Shintō, the native religion of Japan, water is venerated and presided over by Susano-o, god of the sea and storms, Kuraokami (literally, “dark dragon, tutelary of water”), god of rain and snow, and Suijin, the benevolent deity of water itself. A goal of spiritual practice within Shintō is to become like the flow of water, blurring divisions and transcending boundaries. For that reason, many devotees practice purification rituals under waterfalls (taki shugyō).

As a meaningful element in Japanese art and architecture, water is a leitmotif of many Japanese woodblock prints. Katsushika Hokusai, the artist of The Great Wave off Kanagawa, one of the most recognized images in the world, believed that water was sacred and had the power to purify and restore life in accordance with the natural flow of divine awareness. To Hokusai, water represented the flowing of formlessness in the universe.

Katsushika Hokusai (ca. 1760 – 1849)

Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji: The Great Wave off of Kanagawa

Woodblock print; ink and colors on paper

Edo Period, ca. 1829 – 1832

Photo courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Hokusai and his Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji inspired the great, woodblock print artist Utagawa (Andō) Hiroshige. Hiroshige was a plein aire artist who strived to depict nature faithfully. He sketched his landscape scenes out-of-doors and then had the images transferred to woodblocks. Here, he captures a group of travelers caught in a rain storm. Hiroshige recorded this scene while traveling with an official delegation through Ise Province in Mie Prefecture.

Utagawa (Andō) Hiroshige (1797 – 1858)

Fifty-Three Stations of the Tōkaidō: Shōno-juku

Woodblock print, ink and color on paper

Edo Period, 1833 – 1834

Gift of Brigitte and Joseph Lonner

1998.065.001

The image is part of the Fifty-Three Stations of the Tōkaidō, a series of prints commemorating the Eastern Sea route from Edo (present-day Tokyo) to Kyoto. Considered Hiroshige’s most famous series, the Fifty-Three Stations was a pivotal watershed in ukiyo-e, for it greatly advanced the landscape as a key subject of this popular woodblock print genre. [1]

Hiroshige traveled the Tōkaidō in 1832 as part of an official delegation that was transporting horses, a gift from the Shogun to the Emperor as a symbol of his loyalty and as a way to pay his respects to the divine ruler of Japan. The landscape so impressed Hiroshige that he captured the journey in a series of sketches. When it was completed, the Fifty-Three Stations of the Tōkaidō numbered fifty-five, with the extra two commemorating the start and end points. Shōno-juku is the forty-fifth of the Fifty-Three Stations of the Tōkaidō.

Just as Hiroshige is celebrated for his rural landscape scenes, so French Impressionist Gustave Caillebotte is best-known for capturing the daily nuances of life on the streets of Paris. In this larger than life-size scene, Paris Street; Rainy Day, Caillebotte brings us practically face to face with a fashionable flâneur (French man of leisure) and his lady strolling in the rain.[2] With its cropped, zoomed-in angles, sharp tilted ground, and flat color palette, Rainy Day has a grand photo-realistic presence and a sensibility reminiscent of 19th-century Japanese prints, which had become all the rage among the French Impressionists. Like Hiroshige, Caillbotte captured a precise moment in time. As the painting’s simple, straightforward title suggests, Rainy Day takes rain as its main subject and creates around it a snapshot of daily life, turning an otherwise ordinary scene into a timeless, monumental work of art.

Gustave Caillebotte (1848 – 1894)

Paris Street, Rainy Day

1877

Oil on canvas

Photo courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago

Another timeless and iconic work of art that takes water as its theme is Fallingwater, one of the greatest architectural achievements of the 20th century. Designed in 1935 by American architect Frank Lloyd Wright, Fallingwater is a 2855 square-foot house built out over a 30-foot waterfall. The home has strong Japanese elements, particularly the manner in which the structure blends in with its environment, harmoniously bridging nature and man. As Japanese architect Tadao Ando has observed, “…Wright learned the most important aspect of architecture, the treatment of space, from Japanese architecture. When I visited Fallingwater in Pennsylvania, I found that same sensibility of space. But there was the additional sound of nature that appealed to me.”[3] The “sound” that Ando referred to was the melodious song of falling water for which the house is named.

Of the 400 structures that Wright built in his lifetime, Fallingwater is considered his greatest masterpiece. The house embraces the essence of Wright’s aesthetic design philosophy, a concept he originated and called organic architecture, which espoused the construction of structures that were in harmony with humanity and the environment. Wright was also a prolific, and for a time, successful, dealer of ukiyo-e, such as those that Hokusai and Hiroshige made and Caillebotte collected.

As water is connected to humanity and the environment, so Frank Lloyd Wright is connected to Japan and Japanese woodblock prints. When Wright first traveled to Japan in 1905, he purchased hundreds of ukiyo-e, including Hokusai’s Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji and Hiroshige’s Fifty-Three Stations of the Tōkaidō. The following year, he assisted the curators of the Art Institute of Chicago, where Caillebotte’s Rainy Day is prominently displayed, in organizing a retrospective exhibition of the work of Hiroshige, which featured all fifty-five of the Fifty-Three Stations of the Tōkaidō. Perhaps the correlation between all four of these artists and their masterpieces is merely coincidental, but I like to think that the spirit of water, in all its glorious forms, serendipitously linked their flow.

[1] Ukiyo-e, or “pictures of the Floating World,” describes a genre of woodblock prints and paintings that depicted scenes from everyday life in and around the merchant’s quarters of Edo, primarily the districts they created for pleasure and entertainment. Themes of ukiyo-e include beautiful women (geisha and courtesans), kabuki theater, sumo, historical scenes, and landscapes. The term ukiyo is associated with the Buddhist concept of impermanence and the sorrows (uki) of life (yo), a notion that underscores the temporariness of life, youth, and human desire and pleasure.

[2] Rainy Day is a stately painting that measures 83.5” x 108.7” (approximately 6.9’ W x 9’ H).

[3] Tadao Ando, 1995 Laureate: Biography. The Hyatt Foundation. 1995.

A New Face, A Bright Future at Morikami

There’s a new face here at Morikami. She comes to us all the way from Indiana, by way of New Mexico – and Japan along the way – so we are excited to finally introduce you all to our new Chief Curator – Tamara Joy! Tamara has an impressive history of working to preserve and promote Japanese art and culture, and we’re glad to have her on our team. To help you all get to know her a little better, we asked Tamara a few questions – so without further adieu:

Q: Tell us a little about your background – education, professional experience, etc.

As a freshman at Indiana University, I was interested in languages and art, in general. However, after a spending time living and traveling in Asia for a year, I returned to I.U. with a focused interest in East Asia and an absolute passion for all things Japanese. I earned a degree in East Asian Languages and Cultures, viewed primarily through the academic disciplines of art history, anthropology and folklore. I went on to get a Master’s degree, which combined continued study in Japanese arts and culture with a specific focus on textile traditions.

While a grad student, I stumbled upon the idea of museum work through independent study practicums in various museums at Indiana University. I was hooked. My first two jobs out of school included working with Middleton Place Gardens in Charleston, SC and the Wisconsin State Historical Museum in Madison, WI. Anxious to return my focus to Japan, I moved to the city of Yamagata, Yamagata Pref. in northern Honshu to teach and conduct research, specifically on traditional paper-making and various textile dyeing traditions such as indigo and safflower.

After a year, I returned to the States and took a position as Curator of Asian and Middle East Collections with the Museum of International Folk Art in Santa Fe, NM. After several wonderful years there, I was excited to expand my horizons with different types of institutions and collections of Japanese material and was fortunate enough to work with both the Japan Society Gallery in NYC and Museum of Fine Arts in Boston.

In 2011, I had the special opportunity to purchase 10 acres of my grandfather’s property in Bloomington, IN that had been sold out of the family and was in dire need of attention. My husband, Paul, and I embarked upon a two-year vigil of clearing invasive plants and planting trees. During that time, I was hired as Executive Director of the Brown County Art Guild, an organization that was established by a handful of artists in 1927 in the tiny village of Nashville, nestled in the hills and valleys of Southern Indiana. By the 1930s, Brown County had become renowned nationally and internationally as one of the most important art colonies in the U.S. The current Guild Member Artists are still devoted to the tradition of plein air painting and the style of American Impressionism that made the area famous.

Q: What brings you to a Japanese museum and garden in sunny South Florida?

Being invited to be the Chief Curator at Morikami Museum is not only a dream job for me, but it feels as though I’ve been working my way toward this opportunity my entire professional museum career. It will allow me to bring together all of my hard-earned experience and skills, and apply them to this truly unique institution.

Q: You’ve only been with us a short time, but what has been your favorite part of working at Morikami so far?

Even though I am overwhelmed at the moment, I also feel a sense of calm – as if I’m right where I should be – the art, the gardens, the cuisine – I’m enjoying all of it.

Q: Cuisine is one of our favorite things to talk about, so we just have to ask – what is your favorite food?

Having lived in the Tohuku, or the Northern, region of Japan, I’ve become a big fan of soba, a specialty of Yamagata. It’s the ultimate comfort food, served hot or cold. Perhaps I can persuade the Cornell Café to include some dishes!

Q: As you look to the future, are there any projects you are particularly excited to start working on here?

From the start, I’ll be working on AAM (The American Alliance of Museums) museum re-accreditation and collections refinement. I am thrilled for the opportunity to be a part of it.

Q: How do you spend your free time?

My free time used to be devoted to long trail rides on horseback. That’s been replaced by long excursions on the back of a motorcycle with my husband Paul at the helm.

Q: And remind us one more time – how do you pronounce your name?

Tah-Mah-Rah – accent on the Mah. I used to tell people in New Mexico to think “manana” (tomorrow) and they always remembered after that.

We’re excited for all of you to meet the newest member of our team, and we hope you’ll give her a warm welcome to the family!

Guest Post: The Girl with a Cat and Other Paper Tales by Kyoko Hazama

Today, we’re pleased to present a guest post from our Curator of Japanese Art, Susanna Brooks. If you haven’t yet had a chance to see this awe-inspiring exhibit, we HIGHLY recommend it! It’s the perfect addition to any summer outing, especially when the South Florida weather turns a little sour.

Kyoko Hazama may just be Japan’s most imaginative doll paper sculptress. Using traditional Japanese paper (washi) made from the fibers of the bark of a Japanese tree (gampi), shrub (mitsumata), and various plants and grasses (hemp, rice, wheat, bamboo), a sturdier paper than those crafted from wood pulp, Kyoko crafts fanciful dioramas which feature female figures interacting with a hodgepodge of animals. These, she reveals, “are self-portraits.” Kyoko paints, folds, rolls, cuts, and sculpts her paper into whimsical, endearing, self-revelatory vignettes that unlock a unique door into an innocent, magical playground, where clever little ingénues pass the time with a menagerie of horned, winged, and hoofed playmates. Since these tender human figurines represent Kyoko Hazama herself, one easily imagines that the animals in her cosmos are allegorical characters, stand-ins for the real people and relationships that have informed her life.

Kyoko’s miniature paper people and animals reflect also her extraordinary technical abilities as a paper artist, doll-maker, and sculptor. Drawing from pictorial sources and the images that reveal themselves in her mind’s eye, Kyoko manipulates her materials to create the look and feel of real animal fur, antlers and horns, and the velvetiness of young human skin. Her superb artistic skills and imagination materialize tangibly into figures with heartrending facial features and body expressions that evoke a gentle, amiable sensibility and convey a remarkable sense of realism.

There are portraits of Kyoko as a young lady, navigating the boundaries between childhood and adolescence. Room presents a young girl lounging on a green chair, her thoughts seemingly floating far, far away, as three musk oxen stand neatly in a row before her grazing upon the living room floor. Making this scene even more surreal a la Alice in Wonderland is that it plays out inside a wooden drawer.

Similarly, The Walnuts tells the story of a pensive young woman reclining on a red Victorian settee with a pair of squirrels, a chihuahua at her side, and a heap of walnuts protruding from under her sheer, crinkly dress. The girl willfully leans away from the dog, painfully unaware of the squirrels stirring playfully around her, with a vacant stare and reticent posture that silently scream “loneliness.”

Among the most poignant and heartfelt portraits is Rocking Horse, which portrays a young girl laying face down between a rocking horse and a newborn gazelle. The girl’s hand is positioned underneath her right knee and her face is raised slightly upright, mimicking the newborn foal’s stance. As the foal’s mother gingerly, and with a hint of trepidation, approaches the wide-eyed girl, it becomes clear that Kyoko is an outsider.

Another example of animal mimicry is Time Capsule. Here, a young girl sits upon a thick mat of cut vines intent on protecting a large silverback gorilla and her offspring; her back toward the apes, facing the viewer. The girl is crouched low; her long arms extended at her sides and her hands tucked underneath, imitating the pose of the great ape she is shielding.

In Kyoko’s world, the most wild and ferocious creatures of the animal kingdom are approachable protectors and playmates. Warm Sleep presents an Emperor Penguin, the largest and heaviest species of the penguin family, protectively balancing a sleeping infant atop its feet. When an Emperor Penguin lays an egg, the female transfers the egg to the father, who then stores and protects the egg, and eventually the newborn offspring, in its pouch by balancing the egg and/or hatchling on its feet. Here, Kyoko reminds us of this remarkable and tender act of nature.

One of the most disquieting yet charming pairings is Floating Cat, which portrays a little girl sitting next to a giant house cat and staring keenly at the viewer. The young girl clutches a limp green goose in the crook of her left arm, suggesting the flaccid bird is a gift from her giant feline friend.

A skilled doll maker and paper artist, Kyoko Hazama defies artistic classification. She is self-taught and therefore does not belong to an artistic lineage of Japanese craftsmen. It is difficult, if not impossible, to situate her work within the trajectory of art making traditions as defined by conventional art historical taxonomies. Kyoko’s work cannot be positioned within the framework of folk art, craft, or outsider art. Scott Rothstein, artist, writer, critic, and founder of Art Found Out, explains that “her art has much in common with works in all three fields, but her sculptures do not fit into any of these categories exclusively. In Japan, folk artists and craftspeople usually inherit their traditions. The forms they produce are often completely defined with only the slightest room for individual expression.” Thankfully, the remarkable work of Kyoko Hazama overflows, albeit quietly, with self-expression and great technical skill, underscoring her place as an artist of our time, an era in which the lines of categorization are being continually challenged and blurred.

– Susanna Brooks, Curator of Japanese Art

The work of Kyoko Hazama is currently on view at Morikami Museum and Japanese Gardens, Delray Beach, Florida, as part of the exhibition, From a Quiet Place: The Paper Sculptures of Kyoko Hazama, organized by Mobilia Gallery, Cambridge, Massachusetts. We hope you’ll stop in soon! This exhibit runs from now until August 31, 2014.

We Asked, You Answered: The Top Samurai Movies of All Time

Japan’s infamous ancient warriors are the inspiration for Morikami’s newest exhibit and countless classic flicks. We asked YOU for your favorite Samurai film, and came away with a list of decades-old stand-bys and ultra-modern interpretations. In no particular order, here’s the final Samurai film round-up:

1. The Last Samurai (2003)

Why it topped your list: According to Jennifer, “The choice of actors/actresses was perfect and you could tell the amount of time and precision that went in to making the movie. Also, the sets and scenery are breathtaking and just made me want to visit Japan even more. I never get tired of watching it.” In Sean’s words, “Authentic filming in Kyoto and told the actual story of how the samurai’s services were deemed obsolete. A huge turning point in the history and economy in Japan.”

2. Seven Samurai (1954)

Why it topped your list: In Fyg’s words, “It showed the pathos of a samurai’s life and the class differences of feudal Japan.” Joe sums it up this way: “Everything else just tries to be as great as this classic.”

3. Zatoichi (The Blind Swordsman) (2003)

Why it topped your list: “A great example of ‘the art of drawing the sword,'” says Kathleen.

4. 47 Ronin (2013)

Why it topped your list: Jessie raves, “It meshed tradition, culture, and the supernatural into one perfect fantastical adventure! Pure movie magic!”

5. Shogun Assassin (1980)

Why it topped your list: Greg says, “Very moody with great music and action. Tomisiburo Wakayama is the man. Oh, and over-the-top bloody sword fights. Tough to beat.”

We’re just a bucket of popcorn away from a marathon weekend of Samurai-movie viewing – thanks to you! Our recommendation? Get this list into your Netflix queue and queue up here this summer. While tales of the Samurai from the big screen to our galleries hold timeless appeal, our exhibit won’t be around forever – check us out before August 31!

The Lanterns of Roji-en

Toro (literally “light basket” or “light tower”) originated, like many elements of traditional Japanese architecture, in China. Originally, lanterns were only used in Japan to line the paths of Buddhists temples. Stone lanterns were eventually popularized during the Momoyama period (1568-1600) by tea masters, who used them to decorate their gardens.

Many different types of lanterns can be found throughout Roji-en. Some are strategically placed just downstream from a waterfall, overlooking a water feature, or lining a path, but all serve mostly as decoration. Here are a few common styles of stone lanterns found in Roji-en, and where to look for them.

Kasuga-doro. This lantern is a tachi-gata, or pedestal type, and represented a guardian at the entrances of temples or tea gardens. Kasuga-doro lanterns can be seen around the South Gate, Challenger Point, the Yamato-kan bridge and Yamato Island.

Rokkaku Yukimi. This lantern is known as the “snow-viewing” lantern. The upturned roof catches snow, inviting viewers to appreciate a garden in a season when most gardens are frozen. This type of lantern can be found at the Modern Garden overlooking the pond.

Kotoji. Kotoji means “harp tuner.” The two legs of this lantern resemble the tuning forks of the koto, a quintessential Japanese instrument. One leg of the lantern stands on land while the other dips into the water, reflecting the interdependence of land and water. A kotoji lantern can also be referred to as a “wet foot-dry foot” lantern. This type of lantern can be seen in our Modern Garden creek.

Support us while you shop!

Calling all Amazon shoppers! There’s a new way to shop your favorite Amazon products AND support your favorite Japanese garden (us of course!) With AmazonSmile you can help us grow and get the same great online shopping experience Amazon has always offered at no extra cost to you! If you’re ready to get started NOW click here, if you’re still wondering what we’re talking about, read on for the AmazonSmile Q&A.

What is AmazonSmile?AmazonSmile is a simple and automatic way for you to support your favorite charitable organization every time you shop, at no cost to you. When you shop at smile.amazon.com, you’ll find the exact same low prices, vast selection and convenient shopping experience as Amazon.com, with the added bonus that Amazon will donate a portion of the purchase price to your favorite charitable organization.

How do I shop at AmazonSmile?To shop at AmazonSmile simply go to smile.amazon.com from the web browser on your computer or mobile device. You may also want to add a bookmark to AmazonSmile to make it even easier to return and start your shopping at AmazonSmile.

Which products on AmazonSmile are eligible for charitable donations?Tens of millions of products on AmazonSmile are eligible for donations. You will see eligible products marked “Eligible for AmazonSmile donation” on their product detail pages. Recurring Subscribe-and-Save purchases and subscription renewals are not currently eligible.

Can I use my existing Amazon.com account on AmazonSmile?Yes, you use the same account on Amazon.com and AmazonSmile. Your shopping cart, Wish List, wedding or baby registry, and other account settings are also the same.

How do I select a charitable organization to support when shopping on AmazonSmile?On your first visit to AmazonSmile, you need to select a charitable organization to receive donations from eligible purchases before you begin shopping. We will remember your selection, and then every eligible purchase you make on AmazonSmile will result in a donation. You can also click here to start shopping for Morikami,Inc.

How much of my purchase does Amazon donate?The AmazonSmile Foundation will donate 0.5% of the purchase price from your eligible AmazonSmile purchases. The purchase price is the amount paid for the item minus any rebates and excluding shipping & handling, gift-wrapping fees, taxes, or service charges. From time to time, we may offer special, limited time promotions that increase the donation amount on one or more products or services or provide for additional donations to charitable organizations. Special terms and restrictions may apply. Please see the relevant promotion for complete details.

Can I receive a tax deduction for amounts donated from my purchases on AmazonSmile?Donations are made by the AmazonSmile Foundation and are not tax deductible by you.

How can I learn more about AmazonSmile?Please see complete AmazonSmile program details.

Vlogs With Veljko: Growing the Morikami Collections

From art to armor and everything in between, our collections are full of amazing pieces of both historical and cultural significance. But – have you ever wondered how these pieces come to be part of our 9000-piece collection? In this episode of Vlogs with Veljko, you’ll find out how we keep our collections growing – giving you the opportunity to experience Japan’s amazing culture right here in South Florida.